It’s a Friday afternoon—the final day of fall semester classes—and all across campus exams and deadlines loom in the not-too-distant future. But in Fleming 101, the anxiety of finals dissipates as students file in to the lecture hall and settle in their seats for one last class of AS 096: Drugs, Demons and Dancing.

Malevolent in name only, the course is an interdisciplinary exploration of the relationship between the mind, brain, behavior, body and the physical world—commonly referred to as the “mind-body problem.” On this particular day, it’s theatre and dance professor Paul Besaw’s turn to lead the class, which he co-teaches thrice weekly with religion professor Vicki Brennan and psychological science professor Sayamwong (Jom) Hammack. As students make their way into the classroom, he projects a video of an eccentric yet upbeat Korean pop-rock performance that plays gently in the background without context.

Besaw explains later that the artists behind the video reimagined a traditional Korean song and dance style into an unexpected contemporary form that he’s been enjoying lately. “Traditions are always evolving because patterns and habits, sequences and improv happen,” he says. Today he will discuss how patterns, improv, sequences and habits bind his and his colleagues’ various fields of study together. And, because it’s his turn to lead, students will have a chance to “shake out the ‘bleh’ of this week.”

Inherently Interdisciplinary

So, how exactly do religion, theatre, dance, psychology and neuroscience relate? “These seemingly very, very different areas have much more overlap and connectivity than you’d think,” Besaw says. “Once you get into that connectivity, it’s very complex. It’s not easy. But that’s what’s fun about it for us, is teasing that out.”

According to Brennan, they’re all “a natural fit” for analyzing the mind-body problem and collectively offer a unique understanding of what it means to be human from a scientific, humanistic and artistic perspective. Consider, for example, an out-of-body or a religious experience. “Religious experiences are ways of embodying different forms of consciousness or altering consciousness—and so are drugs,” Brennan explains.

Together the unlikely trio have covered topics like emotion, memory, exercise and anxiety, anatomy, pharmacology, philosophy, habits, patterns and instincts and have welcomed guest presenters like dancer Miguel Gutierrez, violinist Daniel Bernard Roumain (DBR) and Dean of UVM’s College of Arts and Sciences William Falls to name a few. Experimental in approach and content, their own questions, conversations and curiosities about each other’s work frequently play out in class in real time, like a demonstration in creative and exploratory thought. “We hope that students see that as part of the way that knowledge about the world is produced, how things get done and how action in the world is accomplished,” Brennan says.

“There are a lot of big questions that people come to college to ask and I think this class shows you that there are different ways to answer them and that they’re all relevant,” Hammack adds.

In fact, that decompartmentalized approach to knowledge is what first-year student and undeclared major Cameron Lopresti ’23 says was most beneficial to him from the course. Taken alongside introductory psychology and philosophy classes, Drugs, Demons and Dancing “mapped on to my entire schedule really well and tied my classes together,” he says, noting that Hammack’s material on brain anatomy directly aided him in a concurrent psychology class and that a unit in philosophy on Descartes—who first addressed the mind-body problem—provided deeper context to the class as a whole.

On the opposite end of their UVM path, graduating English major and psychological sciences minor—and poet—Maddie Strasen ’20 is taking away a greater awareness of habit and improvisation from the class, as well as a memory that will stay with her for years to come. Strasen found herself participating in a spontaneous and powerful two-person performance with violinist DBR during his class visit, when he asked her to accompany his music with a reading of her poetry. On the spot and nervous, she surprised even herself when she agreed to share a poem about systemic racism with nearly 100 other students in the class. “DBR saw potential in me and didn’t hesitate to let me know that,” she says, grateful for the experience.

Professors Paul Besaw, Vicki Brennan and Jom Hammack.

Collective Effervescence

About halfway through the final class, Besaw brings those big, lofty ideas of habit, ritual and improvisation back down to earth, into their very lecture hall. “We walk into the room differently, but most of us sit in the same place every day,” he points out. “We’ve become so predictable. It’s reassuring and satisfying.”

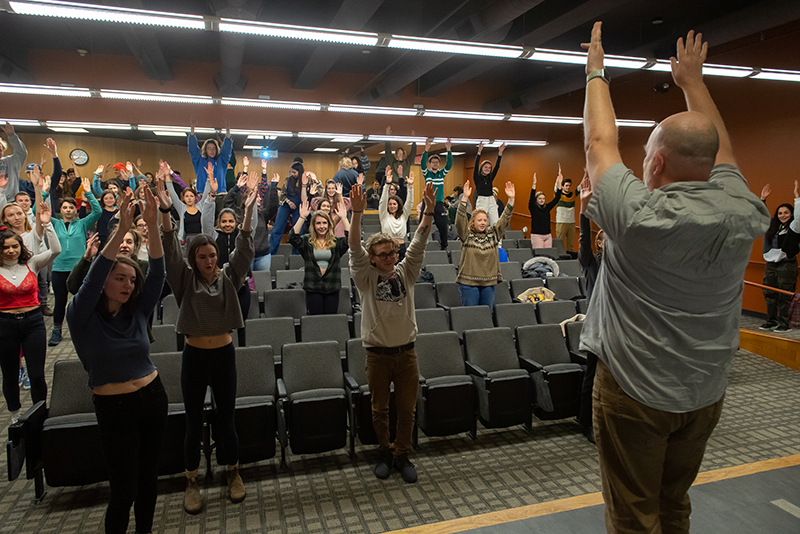

He instructs the class to rise out of their seats and—to the tune of “Send Me on My Way” by Rusted Root—improvise their way around the room. He encourages them to make sounds and noises, to crawl on the ground if they like; just move freely about the room and encounter others. It takes a few seconds, but soon enough roughly 100 students are improvising with ease in every direction. Even Brennan and Hammack do their best to free flow around the aisles and seats and embrace the ephemeral with their students.

Then, all together at once, the room begins to clap in sync to the beat of the music. In the last few minutes of class, Brennan describes this as a moment of “‘collective effervescence,’ when a community realizes its force as a group and celebrates its force together. We move together and celebrate ourselves as a whole,” she explains.

At the conclusion of the inaugural class, Besaw, Brennan and Hammack huddle together to thank their students for going along with the experimental course and the university for encouraging collaborative classes like this to come to fruition. They’ll be offering the course again next fall and, in a final demonstration in creative and exploratory thought, they turn the remainder of class back over to their students—what else are they curious about? What more do they want to know?

“Where did the name of the class come from?” a student asks right out of the gate. Brennan confesses that though the desire and need for the interdisciplinary class had been on their minds for a while, a name for it hadn’t. “I said, as a joke, ‘You could call it Drugs, Demons and Dancing, because that’ll get everybody interested.’ I guess it worked.”

Source: UVM News